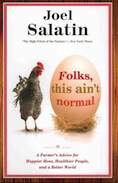

RATING: 8/10

A book that reminds me of how far detached from the food system I really am. Every bit as shocking as Food Inc. and then some. It’s a call for a return to “normal,” adapting to biological life systems as nature intended. A great book not only for detailing farming and the injustices, but looking at how distorted are reality really has become culturally.

Notes:

A restaurant that only wants one cut of meat is of little benefit to a small-scale producer who has to sell all the meat from an animal. Similarly, making a farmer with a husband-and-wife labor force fill out reams of paperwork and forms before they can deliver one bite of food to a franchised food store is a cruel and unusual punishment.

The small farmer’s competitive edge comes from producing a highly flavorful, high-skill input, seasonal product that can be marketed through a short, inexpensive, distribution chain. Local marketing not only fits this requirement but is usually essential for a profitable, self-sustaining, small-scale farm.

Using sweat equity, he has built a two-million-dollar-a-year food business without any government loans, assistance, or subsidies.

Most of us have been so conditioned by the industrial food system that we don’t realize the conflict between our belief system and our expectations. For example, don’t expect fresh, unfrozen, grass-fed beef and chicken in the dead of winter at your local store or restaurant.

Our culture now denies young people the very activities that build their self-worth and incorporate them as valuable members of society. Rather than seeing children as an asset, we now view them as a liability.

Our societal paralysis to leverage youthful energy in a more meaningful way than soccer, ballet, and video games indicates profound imagination constipation. This protective timidity that denies our young people risk and self-actualization keeps them from attaining emotional, economic, and spiritual maturity.

I like a great ball game as much as anybody, but all game and no meaningful work creates an unbelievably jaundiced view of life and our role in it.

If your tomato plant dies because you failed to water it, you don’t count to ten and watch a miraculous resurrection. Death is final. It’s over. The hubris with which our young people enter life, living in this world of replacement and limitless instant gratification, engenders an arrogance toward life and ecology that is both scary and dangerous. No fear is the mantra of fools.

The garden teaches balance. No gardener plants only one thing. Yes, industrial agriculture does that, but no gardener would think of such nonsense. Gardeners balance high plants with low plants, top growers with bottom growers, vegetables with flowers. The gardener learns about crowding plants, about earthworms, soil tilth, and a host of comparisons and contrasts that create a vibrant place.

–Grow things . . . anything. Indoor grow lights are still magic, and can bring

sunlight indoors for remarkable discoveries.

–Brainstorm entrepreneurial child-appropriate businesses—hand crafts, repair, tutoring, calligraphy, customized invitations, cleaning homes, mowing lawns, picking up rocks, hoeing weeds. The list of possibilities could fill many pages. Don’t underestimate the creativity and resourcefulness of your sixteen-year-old unleashed on the community. Stay out of the way and let her run.

A culture that creates a negative value on children has to be the least creative culture on earth.

The cow, perhaps more than anything else, represents civilization. Domesticating this multipurpose beast that can turn lowly grass into meat, milk, power, clothing, cordage, tools, lubricant, cleansers, and roofing materials arguably defined civilized living opportunities. Ecologically, the cow restarts the photosynethetic biomass accumulation process.

This is perhaps one of the biggest misunderstandings people have about farming ecology. In a desire to get rid of the cow, they want to substitute plants that require tillage. No long-term example exists in which tillage is sustainable. It always requires injection of biomass from outside the system or a soil-development pasture cycle.

Tillage or stirring the soil, burns out organic matter due to the hyperoxygenation it creates. While this offers a tremendous amount of energy to a growing crop like squash, corn, or wheat, it comes at a price in soil degradation, and especially nitrogen retention.

The fact that life requires sacrifice has profound spiritual ramifications. In order for something to live, something else must die. And that should provide us a lesson in how we serve one another and the creation and Creator around us. Everything is eating and being eaten. The perpetual sacrifice of one thing creates life for the next. To see this as regenerative is both mature and normal. To see it as violence that must be stopped is both abnormal and juvenile.

No life can exist without sacrifice is a profound physical and spiritual truth. And the better the life, the greater the sacrifice.

God designed chicks, therefore, with a unique ability to survive just fine without feed and water for three days so that all their siblings can hatch before the mother hen takes them on their first meal outing. In case you’re wondering, chicks don’t nurse their mothers. The mothers take them to food, and from day one, chicks feed themselves. How about that, moms? Pretty cool, huh? Chicks are not human.

–This unique quality allows chicks to be shipped through the mail without hurting them.

The function that herbivores play, for example, in stimulating biomass accumulation is both powerful and real. Chickens have historically converted kitchen scraps into eggs. Pigs have historically scavenged domestic waste products as varied as whey, offal, forest mast, and spoiled grain. That a large percentage of landfilled material is animal-edible food waste should strike us as criminal. Rather than showering landfill administrators with greenie awards for injecting pipes into the anaerobic swill to collect biogas, we should be cycling all that edible waste through chickens and pigs so that it never goes to the landfill in the first place.

–Traditional recycling like this was foundational to the economy of a farmstead or village prior to this blip that we now know as cheap energy.

Nobody in the world goes hungry due to lack of food production. It is distribution and other problems that create starvation. Because they can eat perennials that do not require tillage, herbivores are always preferred in impoverished societies. This is why the most efficacious famine-relief agencies I’ve been privileged to work with, like Heifer Project International, are founded on livestock. If you really want to help impoverished people, get them started in animal husbandry.

I know a lady in North Carolina who lives next to a yogurt factory. She raises pigs—that was the occasion of my acquaintance—on rotten milk. She said the factory throws away tractor-trailer loads of milk all the time—she can get as much of it as she wants, for free. Anyone who has worked in industrial food processing facilities knows that this is the case. If all the whey generated from cheesemaking went through hogs, like it did historically, we could produce the pork as a salvage and still get all the meat and manure. As it is, most of it is just thrown away or energy-intensively processed into organic fertilizer for potted geraniums in the homes of middle-class Americans.

As a culture, we think we’re well educated, but I’m not sure that what we’ve learned necessarily helps us survive.

Dear folks, chickens don’t need roosters to lay eggs. They need roosters to hatch eggs, but not to lay them. Just like women don’t need men to lay eggs; they just need a man to hatch one.

Straw is the stalk and leaves of a small grain plant. Stover is the leftovers of a corn plant. Hay is solar-dried forage. When forage gets tall, you cut it and let it lie in the sun. The sun dehydrates it so it can be packed together without molding. Hay is edible for the animals and straw is generally used for bedding because the edible part came off in the grain, which is really a big fat seed. If forage is packed together before it dehydrates, and you exclude the air with airtight packaging (silo, plastic) it ferments, making silage.

–In order to get hay equally dried, it is windrowed to let the air blow through it and get the underneath leaves turned up to the drying sun. A windrow is a long tube of hay. A baler picks up the windrow and forms the hay into packages: round bales, little square bales, little round bales, or large square bales. Each of these has a different machine and different reason for use.

pg 37 – memorize cow differences

Realize that agendas drive data, not the other way around.

Read things you’re sure will disagree with your current thinking. If you’re a die-hard anti-animal person, read Meat. If you’re a die-hard global warming advocate, read Glenn Beck. If you’re a Rush Limbaugh fan, read James W. Loewen’s Lies My Teachers Told Me. It’ll do your mind good and get your heart rate up.

The first supermarket supposedly appeared on the American landscape in 1946.

Roughly half of all the human-edible food produced on the planet never gets eaten. It spoils in warehouses and shipping containers. It bruises during transportation. It exceeds sell-by status in logistical distribution snafus. It doesn’t get to the refugee camp because a group of thugs holds a Red Cross truck at gunpoint.

Nobody goes hungry because of lack of food; they go hungry due to a lack of distribution.

Every single one of the African presenters I heard said something like this: “What is killing our local food system is cheap Western dumping. We have plenty of resources. We have plenty of knowledge. We have plenty of workers. If you westerners (primarily America, often via the United Nations and other relief organizations) would just stay out and quit displacing our indigenous economy and food systems with poor-quality commodities, we can feed ourselves, thank you.”

When a container of foreign goodies arrives in the village, everyone mobs the freebies and takes the Western handouts. This collapses the local business and these displaced go-getters become the famous warlords we in the West have all learned are the nexus of all those people’s problems. This same story has been corroborated since and makes me careful about how I help. Help is not always a handout. Help can also be a butt-out. And help is not always about material possessions. Sometimes it requires faith in people to go through their societal evolution, that they can indeed learn from their mistakes.

In my experience, some of the most normal-living people are the ones who make the least noise about it.

The average age of America’s farmers is now approaching sixty, but thirty-five years of age is considered by business analysts to be the median age of the practitioners in a vibrant economic sector. Farming has not seen that age in a long, long time.

Albert Einstein said you cannot have construction without first having destruction.

“We can’t even begin talking about local food until we get enough culinary expertise to know what to do with things when they are available. Nobody even knows how to cook anymore.” Sadly, he is right. Cultivating the domestic culinary arts may be a bigger issue in restoring food normalcy than distribution, production, or anything.

Everyone has heard the saying, “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right.” I have news for you—that’s wrong. The truth is this: “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing poorly first.” Who ever does anything right the first time? And yet we’ve had that “worth doing right” drummed into our heads for so long, we’re afraid of doing something new lest we make a fool of ourselves or have a flop.

Making the kitchen the focal point of domestic camaraderie exceeds anything else. When families begin placing importance on food, they make a political, societal statement. To actually care about food, to think about it, to see it as a conscious act is indeed a revolutionary thought in today’s world.

A lot of people don’t realize that our anatomy coincides with that of lambs, pigs, and cows.

–If you really want this to make sense, get down on all fours like you’re going to take your kids for a horsey ride and it will be obvious. The butcher, then, breaks down the carcass into the various cuts that he pretties up into rounds and squares. In doing so, he discards corners and odd pieces into what is called trim. He runs this trim through a grinder, creating ground pork. Adding spices to that ground pork is what makes it become sausage. Isn’t that profound?

Our bodies have never, never, ever eaten things that were not pronounceable until the last few decades. Until then, it was understandable, egalitarian—anybody could learn how to cook and everything in food could be grown in a garden, a field, or a forest. It could be picked, threshed, cut. It was not manufactured in a laboratory.

We’re only 15 percent human and 85 percent nonhuman.

Every one of us, whether we like it or not, is utterly and completely dependent on an unseen community, an invisible world. We pamper and primp to make the visible body more appealing, but what are we doing to beautify our unseen world? In our Western Greco-Roman compartmentalized fragmented systematized linear reductionist individualized disconnected parts-oriented thinking, we tend to disassociate the seen from the unseen. We do so at our own peril. We are all, every one of us, simply a manifestation of this invisible world.

Creating food out of things that can’t be made in a home kitchen sends confusion into our physical being while sending confusion into our mental being. Unable to make the stuff, we withdraw from food knowledge and awareness. How many times have you heard people respond to the question, “Do you know what is in that?” with this answer: “I don’t want to know.” This isn’t simple denial; it’s too arduous to understand. It’s the classic escape from what is too complicated to learn. The more complicated a subject, the slower we are to embrace learning it.

Life is not sterile. Biology is not sterile. Things that won’t rot, or won’t decompose, or a disposal system that impairs decomposition, all characterize inanimate things, mechanical things. We are surrounded, inside and outside, with bacteria and decomposition. The entire principle of recycling hinges on the ability of something to decompose.

When we masticate that carrot between our teeth, we are taking the life of that carrot, crushing it, flooding it with bacteria-laden saliva, and decomposing it in our own bodies, with our own microbial community, which extracts new life from it and builds cells in our bodies, bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh. The spiritual metaphor is powerful: Without sacrifice, life cannot exist. Whether it’s plant or animal, something must give its life for life to occur.

Until electric fencing, farmers could not efficiently handle their livestock like nature did with large herds, migratory patterns, and predators.

When it comes to the soil, if you take care of the carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, the NPK will essentially take care of themselves. But you see, the chemical companies don’t make money on carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. Those are things the farmer can manage himself. And the agronomy professor’s research is financed by a chemical company or some other industrial conglomerate, so the lecture will necessarily adhere to academic requirements and deal only with NPK.

I think if we’re ever going to be really creative about solving issues, we need to reestablish what is historically normal. Until we have some sort of benchmark, we don’t know how to measure progress. We may think we’re going forward and actually we’re going backward.

What if we had as much excitement going on in our kitchens as we think we might find doing some discretionary traveling?

I’m not opposed to travel and I’m not a hermit, but do we really have to move around as much as we do? I think the reason we need to travel more is because we don’t have anything exciting to do at home anymore. But if we’re gardening, cooking, and cottage-industrying—home can be as exciting as any discretionary destination. We’ve divorced our own homes as the centerpiece of life, and that disunion manifests itself in running elsewhere looking for satisfaction. That takes a lot of energy. What can be more exciting than watching kitchen scraps turn into eggs via a couple of intermediary chickens?

Enjoy your family and nearby friends. Play music. Write books. Read books. Start a community discussion group. Have a spelling bee, a community variety show, an art contest. Our compartmentalized world is so segregated that we’ve come to think that entertainment can only come from industrial entertainers.

Henry Ford made a car body out of hemp. The material was stronger, lighter, and more durable than sheet metal.

Green thinking is eliminating the confinement facility to begin with, eliminating the motors once and for all, turning the cows out onto pasture, using a simple composting system, and eliminating the need for 90 percent of the energy in the first place. That’s green thinking.

Simple regenerative, locally appropriate systems always work better than high-tech bureaucratic know-it-all Western dumping.

How did people survive before the building inspection department? Could it be that builders were responsible for their buildings, and their pride kept them true to engineering necessities?

How do we encourage personal responsibility in craftsmanship? I submit that we encourage personal responsibility like we encourage it in our children. If my child’s homework becomes somebody else’s grade, my child won’t put the effort into it that she will if the grade is her responsibility. If a building collapses and a builder can say, “It’s the inspector’s fault because he didn’t tell me,” we won’t encourage personal responsibility. Creating a climate of performance excellence requires personal responsibility.

While it may seem like environmentalist heresy to call current thick forests abnormal, the reality is that rich North American soils developed during centuries of widely spaced trees surrounded by grasses.

In our day, the most basic necessities to maintain life receive scarcely a thought. Water, food, shelter, energy, clothing—as a culture, we don’t give these any thought. Somebody else takes care of all that. Just let me go shopping, or watch my wall-sized flat-screen TV. Our visceral relationship with life’s fundamentals has been severed, and the result is an arrogance, a cavalier attitude toward the foundations of life.

The thinking that created the thinking that thinking people think water use should be allocated based on its gross dollar returns is thinking reflective of jaundiced thinking that indicates improper thinking in the first place.

The whole point of tillage is to eliminate vegetation already growing on the soil to create a receptive environment to plant seeds.

Tillage is actually painful for the soil. It superoxygenates the soil, exposes it to the weather, and burns out organic matter.

Nature builds soil with perennials, herbivores, and periodic disturbance, or pruning. Plants are solar collectors. A plant is 95 percent sunlight and only 5 percent soil. That means if you pick up one hundred pounds of plant material, ninety-five pounds was created out of sunlight and thin air, so to speak, and only five pounds came from the soil. This is obviously a magnificent process in which the earth, if properly managed, should be gaining soil, indeed gaining weight, every day.

Even without tillage, the soil recuperation between grain crops is four years.

The herbivore is a four-legged portable fermentation tank, a sauerkraut vat, if you will, turning biomass carbohydrates into meat and milk. This fermentation, or digestion process, gives off less CO2 than the biomass would if it were allowed to simply decay on the stalk.

-The cow, or domestic herbivore if you will, is the most efficacious soil-building, hydrology-cycling, carbon-sequestering tool at the planet’s disposal. Yes, the cow has done a tremendous amount of damage. But don’t blame the cow. The managers of the cow have been and continue to be the problem. The same animal mismanaged to abuse the ecology is the greatest hope and salvation to heal the ecology.

-The critical thing to understand is that grazing can be done in a way that builds soil and heals the land, or it can be done in a way that destroys the land. Grazing is not inherently good or bad. It is the grazing management, the pattern, that makes it ecologically positive or ecologically negative. Nomads have certainly destroyed plenty of land through overgrazing, as have American farmers.

The acceleration of environmental degradation in the last century is not because we have too many cows. It is because we have too few cows and the ones we have are too often locked up in massive feedlots eating chemical-based annual grains (corn and soybeans) rather than out grazing on perennial forages like their predecessors. The abnormal acceleration of cow-induced ecological degradation is symptomatic of widespread disregard for historical ecological normalcy, which required that grazing animals do just that: graze.

The only, and I repeat only for emphasis, reason that the current grain-fed beef and dairy factory system works is because petroleum is cheap. Take that out of the equation, and the whole thing collapses. Indeed, if all herbivores returned again to perennial pastures using the biomimicry outlined above, not only would the meat and milk be of superior quality, but farmers would make more money and soil would build instead of eroding. And carbon would be sequestered in the soil instead of being pumped into the atmosphere via cultivation and petroleum use.

If you ever smell a stinky farm, be assured that it is wasting its most precious recyclable nutrients and depriving the land of important fertility.

If all the lawn clippings, municipal leaves, and yard wastes generated in the last seventy years had gone onto farmland instead of into landfills, we would not have needed the chemical-based fertilizers we used, and that would have kept the soil from being destroyed. If our grain still had all its stems and leaves, so that when we harvested grain it also generated twice as much carbonaceous straw, the carbon cycle would be in sync. The soil would rejoice.

Our fuel costs per dollar in gross sales are only 10 percent of an industrial farm’s fuel costs as a percentage of gross sales.

Much of the alleged pharmacological progress in the early 1900s was to reduce diseases created by an abnormal feeding, housing, and sanitation regimen. Had it not been for these abnormal farming systems, today’s second-generation pathogens would not have developed.

-What do I mean by second-generation pathogens? I mean all those Latin squiggly words like E. coli, salmonella, campylobacter, and Listeria. And I would include things like MRSA and C. diff. in hospitals and antibiotic resistance that is becoming more and more rampant.

We’re hardwired to blame somebody or something else for our deficiencies. It’s natural to focus on germs instead of immune systems.

Germ theory works great in trauma, where you’re dealing with a tsunami of enemy forces. But in a day-to-day wellness maintenance regimen, the terrain is the way to go.

Pg 216-217 describing the industrialized food system

When industry representatives effuse to me, “Look how much one farmer can produce,” I like to add, “Yes, the farmer plus a host of technicians, mechanics, field reps, drug companies, construction crews, pollution abatement workers, and logistics managers.” These are not stand-alone self-contained farm operations. They are monstrosities with a host of personnel behind the scenes making sure things function.

How have we arrived at this kind of thinking (GMOs)? It’s because in our Greco-Roman Western compartmentalized systematized fragmented individualized disconnected parts-oriented worldview, our culture views life as fundamentally mechanical. It is interchangeable parts. It is a rearrangement of protons, electrons, and neutrons. It’s a huge Tinkertoy set, or a big box of Legos. It contains no mystery. No ethics. No morality. Respect is not necessary.

I am not a scientist. And neither are most people. I learned long ago to lead with the heart rather than the head because, ultimately, all of us make choices based on emotion. We really aren’t rational beings. But we know what we know. We know what we’ve seen. Our perceptions are a collection of experiences and exposures.

High capital-intensive, nontransparent, corporate-controlled solutions will not, in the end, make life better for the peasants. Never has and never will. At our farm, we have a 24/7/365 open-door policy for visitors. Anyone may come unannounced anytime to see anything. That’s our level of open sourcing. Our farm freely shares techniques, rations, everything. In the big scheme of things, we don’t even own the land; we’re just custodians for a few years.

The percentage of American per capita income spent on food is the lowest of any country in the world.

–Another interesting downtrend is the portion of the retail dollar that goes into the farmer’s pocket. Just forty years ago, that was nearly fifty cents on the dollar. Today it averages only eight cents, and it’s continuing to trend downward.

With so much food prepared outside the home, how could the price have dropped like this? The answer: Commodity prices have fallen. In most commodities, the price has steadily dropped over the past fifty years. To keep up with inflation, wages, energy, and machinery costs, major commodities would need to be three times what they are. To keep up with land costs, they would need to be twenty times what they are. With this abnormal plummeting of farm gate value, our culture has created a bottom-feeder attitude toward farmers.

For decades we’ve shipped our best and brightest off to town to become white-collar doctors, lawyers, accountants, and engineers, and reserved food production to society’s dolts. Does that make sense? Do we really want society’s bottom feeders to be in charge of our air, soil, and water? Compare that with the culture in Spain that manicures cork forests to grow the world-famous acorn-fattened black-footed hog. In that culture, the man who knows how to prune the cork trees is revered as much as the medical doctor.

Processed food is expensive. Even fast food is expensive. To get the same nutrition out of one pound of primo Polyface salad bar ground beef, you would need several Big Macs, and they would cost way more than $4.50.

Suppose the nation had five auto manufacturers and the government decided to subsidize four of them to the tune of $5,000 per automobile. Would it be fair to scream at the fifth one about their high prices? Of course not. And yet that is exactly what people do when they accuse the local, ecologically based food system of high prices.

“We’re charging the true cost of goods and labor, not some artificial one. The truth is that the cash register price for regular industrial food at the supermarket—processed or not—is a lie. It does not represent the subsidies. The biggest subsidies are not direct payments to farmers, they are the tab society picks up for externalized costs. The costs of 500,000 cases of foodborne bacterial diarrhea that Americans will get this year from dirty food. What’s the price on a case of diarrhea? I don’t know, but I guarantee you if those were added to the supermarket cash register, food wouldn’t be as cheap as it is.

Here at Polyface and the farms like ours, all the costs are figured in. We’re not creating a Rhode Island–sized dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. We’re not making three-legged salamanders and infertile frogs. We’re not killing earthworms; we’re growing them. We’re not destroying the soil; we’re building it. We’re not increasing atmospheric carbon; we’re sequestering it in the soil where it belongs.

The collateral damage from concentrated animal feeding operations, pesticides, herbicides, and toxic manure lagoons has not even begun to be tabulated. It may be decades if not centuries before the true cost of this abnormal food system gets tallied. I tell people our Polyface food is the cheapest food on the planet, because all the costs are figured in. It’s not a price charade.

Farmers generally have all their equity tied up in their land. While others put money in stocks and bonds, treasury bills, IRAs, gold, silver, or other investments, farmers plow everything back into the farm. The farmland represents the farmer’s investment portfolio.

I have a friend who wanted a woodworking shop next to his house. He happened to be located in an agricultural zone. No can do. Oh, he could build the woodworking shop, and he did. He can do tremendous work. He can fix chairs, build furniture. Nice work. He just can’t sell anything or charge for his services, because that’s a business, and we wouldn’t want a business on agricultural land.

I’ve heard that once land is developed, it’s gone forever. Don’t believe it. Where are the ruins of ancient civilizations? If everybody vacated New York City today, within three years you would see trees sprouting through sidewalk cracks. Within a decade you would see vines growing up the sides of the skyscrapers. And within a hundred years it would be a forest. In truth. I have no desire for that to happen, but I’m using perhaps the most extreme development example to debunk the notion that development destroys land forever. It does not. All those suburbs can just as easily become farms again.

Nobody should need an Environmental Protection Agency to say that polluting the river is bad. If polluting the river is wrong, let the perpetrators be brought before a jury of their neighbors (peers) to assess a penalty. That keeps the politicians out of it.

What we need is for businesses—and anyone else for that matter—to be scared to death to hurt a neighbor. That should include the military, the president—anybody. If some big daddies get a spanking, maybe they won’t get so big for their britches.

–Third, no paradise exists this side of eternity. No policy is all positive without any negatives. The trade-off to food that heals the land and heals the people is that it is more expensive at the cash register. The advantage is you don’t go to the hospital as much.

–Well then, maybe we don’t need as many hospitals. Oh no, Humana stock falls. But instead, cottage industry thrives. Some nurses and doctors could open mini-practices in their neighborhoods and garden on the side. I’m trying to help us all understand that everything relates to everything. You can’t have a change in policy without creating a domino effect.

One big fear facing the heritage-based food community is the anemic bacterial tolerance of people. Due to the fear of litigation, most food processors confuse safe with sterile. I have news for you: Our bodies do not want sterile food. Plastic is sterile. Glass is sterile. Sterile is not biological. Sterile does not feed our three-trillion-member internal community.

Jesus never invoked the government to help anybody. He invoked His followers to be Good Samaritans, and to help the needy, to make room for children. He never encouraged anyone to use the government to those ends. Why? Because forced charity is not charity at all. If the government comes to me with a gun and takes my wealth to give to some charitable cause, regardless of how noble, the forcible removal of my contribution does not make this a charitable act.

I’m not responsible for my health and the food I eat, then what else am I not responsible for? My education? My retirement? My income? My children? My job performance? Maintaining my house? Maintaining my automobile?

If industry can’t hide behind inspectors anymore, it will force the industry to be cleaner because now it’s their own responsibility instead of someone else’s.

A $500 test once a week is nothing if you’re running a $500 million processing plant. But if it’s a $1 million mom-and-pop like T&E Meats, that’s the entire week’s profit. This is a part of food safety that the sincere-minded consumer advocates don’t understand. The reason America has lost half of its community-based processing capacities each of the three times the FSIS has been overhauled is because each time, the increasingly onerous regulations have run the little guys out of business.

We’ve become too sophisticated for our own good. We’ve analyzed and studied and data-processed until we’ve lost sight of the big picture. The big picture is about leaving the door open to new ideas and out-of-the box solutions.