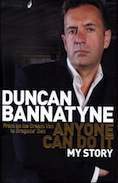

RATING: 7/10

The biographical story of Duncan Bannatyne, the guy from the Dragon’s Den. I knew little about him before reading except he got a later start in entrepreneurship. A great look into a millionaire who didn’t have contacts, money, expertise, or a USP —he just hustled and was ambitious. Some of the later chapters wean a bit, but overall highly recommended.

I had an incredibly poor childhood, I left school without a single qualification and spent my twenties doing a string of dead end jobs. It wasn’t until I hit thirty that I took my career seriously and by thirty-five I was seriously rich. Contrary to the advice in any business book I’ve read, I made my money without sector expertise, contracts or capital. I never had a USP, never had a “first mover advantage” or invented anything, and I didn’t even do anything unique or that someone else couldn’t have done. What I did have was a Yellow Pages and some determination and that’s all it takes.

It was almost as if I was enduring my childhood while I waited for something bigger and better to come along.

People ask me what gives me my drive: I want to know why other people don’t share it. The conclusion I’ve come to is that every other ice-cream seller in the north-east must have been happy with the status quo. I wasn’t: I wanted more.

You have to stand up to intimidation. If you show any weakness it will be exploited.

I can see how some people benefit from networking, but for a single minded entrepreneur like me, there was no point: my business success was forged from the strength of my personality, not my contacts.

It wasn’t a problem for him as he has skills I don’t have—he’s great with people and pays attention to detail, attributes I know aren’t my strong point. What this teaches me is that you can run a business any way you want to, but to be successful you must recognize your weaknesses and employ people with complementary skills.

I’ve said all along that I’ve made it in business without contacts or a network, but I did have a telly and I did buy a newspaper, and they were pretty good substitutes for picking up leads.

In business, it doesn’t matter if you come late to the market: if you can do it better than your competitors, you can still make money.

Most people have an idea for a business at some point in their lives, but they don’t do anything about it—that’s really the only difference between entrepreneurs and everyone else.

We see so many would-be entrepreneurs who are asking for backing because they’re not prepared to back themselves. They don’t believe in their idea enough to borrow the £50,000 they’re asking for, or they’re not prepared to offer their house as security, or even give up their jobs. They say they don’t want to take the risk.’ And that’s when I tell them ‘I’m out’ because I know an entrepreneur in debt is an entrepreneur in business.

Being free to look to the future and work out how to grow is key to growing a business: it’s what the chief executive officer is there to do. If I had been consumer with how each manager was running their department, or had got personally involved in details like which bed linen we bought, I would have never been able to look for new sites, analyze the competition, negotiate new contracts or any of the other things that made use better and kept us competitive. If my thoughts were uncluttered by the minutiae of the business, then I was better able to the bigger picture, to lead and problem solve.

It’s impossible to think big without thinking complex.

You can only really learn about business by being in business.

The best opportunity is the one you understand.

One of the many similarities between the care-home and day-care sectors is that they’re both serving the public NEED, so neither business has to spend very much on advertising and marketing as customers come looking for us. In some businesses you need to spend the bulk of your money on client acquisition, and as marketing is imprecise and expensive, it’s much better if you can find a direct route to your customers.

On pitching to investors:

Give me a pitch I understand: Don’t over complicate things—tell me simply what you do, why your idea is better than your competitors, how people will buy your product or service and why you’re the right person to lead your company.

Be honest and open: Give me a simple, straightforward answers to my questions. Don’t hide behind jargon, impossible promises or pie-in-the-sky-talk. If you come across as sly or deceitful, you’ll leave with nothing.

Know your numbers: if you don’t know how much your product costs to make, what it retails at, your profit margin, your investor’s return on capital or how many competitors you have in any given market, then I’m not going to be convinced by you. I want hard figures based on plausible projections.

Tell me the exit strategy: if I invest in you it will be a partnership you my money and input, and in return you give me a return on my capital. That’s the deal, so I want hear how and when I’ll be taking my profits.

I’m immensely proud to say that I’ve achieved everything without being ruthless. You don’t need to be ruthless in business. All I ever was buy land at a price other people wanted to sell it for, give builders a contract at a price they suggested, and then people used my services at a price I advertised them at. What’s ruthless about that? I’ve also done a lot of my work in industries—nursing homes, day nurseries and health clubs—that have made life better for people. Business really, truly isn’t about being ruthless. Single minded, sure; but ruthless, no way.